THE LIVER TRANSPLANT UNIT

Text by Erin Stone

Photographs by Ariel Subira

Video by Lucas Andrade

At 8 o’clock in the morning Jorge Martins de Aguilar is woken in his home in Duque de Caixas by a call about a liver. The one he was born with is dying, bloated and scarred by cirrhosis. But today one that works has become available—and it matches his genotype.

* * *

Meanwhile at the same moment, 25 miles away in Tijuca, Rio de Janeiro, a team of 2 surgeons is already on their way to collect the brain-dead man whose body houses a still-working liver, the first step in a typically 16 hour process of preparation for the surgery, the transplant itself, and post-op care. The medic center is notified so they can prepare for the patient’s arrival and so are 2 anesthesiologists and 3 surgeons. They must first receive an “okay” from the surgeon responsible for removing the donated liver. When—and if—he says the liver is good for transplantation, all hands must be ready to begin the process immediately. But for now, they wait.

And so, it’s just another day for the medical professionals who work at Hospital Sao Francisco. Two statues, one a gleaming marble of Maria Mae de Deus, stand in greeting at the entrance of the tall white building that is the hospital’s main entrance. Sao Francisco’s campus is quaint but large, and it shines on this sunny day, the mountains that are home to the Tijuquinha favela sloping above it, still hazy with morning fog. A nun, also cloaked in white, walks slowly up the path towards the entrance, loosely clasping her hands in front of her, perhaps on her way to visit patients. Orderlies wheel patients down the long halls, which look heavenly as the soft morning light streams in through the tall windows, illuminating the doctors in their white coats, making the blue scrubs of the nurses, orderlies and surgeons glow. The surgery center resides in one of the buildings that surround the sunken courtyard, lush with palm trees and other tropical plants. The chirping of birds and people chatting echoes across the courtyard. On the upper tier overlooking this setting, where the main quad and cafeteria are, the hospital church nests—a woman crosses herself as she passes it. It is surreal, divine. Sao Francisco really is a beautiful place—and the largest public hospital in Rio.

* * *

By 11 am Jorge’s new liver has arrived at the hospital and a surgeon is examining it to make sure it will in fact be a good fit for him. The hospital has grown busy by now. Patients wait for their appointments, sitting on the ground or on the thin white benches that line the halls. They often have to wait for hours, making even the simplest doctor’s appointment a full-day affair. Brazil’s public Unified Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde, or SUS) may be slow, but it does work. Ever since Brazil’s constitution declared health as a citizen’s right and a duty of the state in 1988, the public health system has grown massively, serving more than 75% of a population of about 200 million. Before the 1988 constitution, half of Brazil’s population had zero health coverage.

The idea is good but Brazil’s public health system is understaffed given the private system draws more medical professionals with its higher salary and better hours. But Hospital Sao Francisco is one of the lucky ones: it has more doctors than the average clinic and attracts professionals that have both a passion and stamina for what they do—like those who will perform Jorge’s transplant.

Outside the surgery center, the three surgeons and anesthesiologist, all young guys, stand joking and talking, enjoying the fresh air before they head in to prepare for Jorge’s liver transplant—the surgery alone can often last 8 to 10 hours. To an observer, their relaxed demeanors seem hard to believe before performing a life-altering surgery. But this is routine for them—they usually do 2 or 3 liver transplants each week.

* * *

In the building across the main quad from where the young surgeons stand, Jorge sits quietly in a small dim room, Quarto 309, answering occasional questions from the nurse. He talks quickly and seems shy and a bit nervous, though he maintains a friendly smile. His voice is high-pitched and gravelly, at times whistling through the gap between his front teeth. Jorge is a petite guy, with thin limbs and face but these features don’t match the size of his water belly, which protrudes perhaps a foot and a half—his entire core bloated and round, the striped white and blue dress that is the surgery patient’s uniform stretched across it like a house tented for termite extermination. Hepatitis C, though, cannot be exterminated by a liver transplant. It will only fend off the gnawing the liver has endured for a little more time. But Jorge’s cirrhosis is a result ofa different disease—alcoholism—which sets him apart from most liver transplant patients in Brazil, whose livers have been destroyed by Hepatitis C and/or other forms of viral hepatitis.

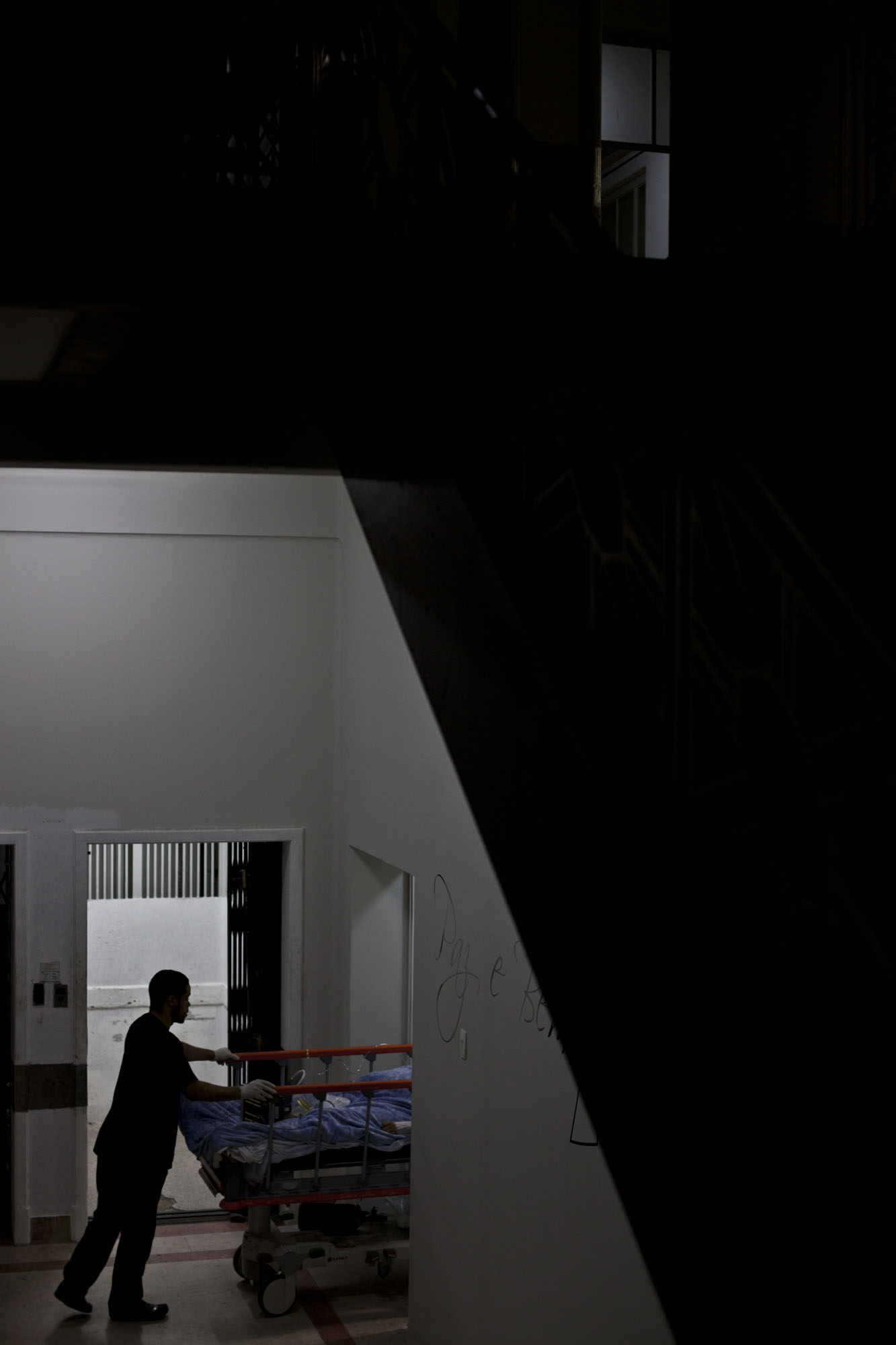

When the time has come, Jorge lifts himself onto the trolley, carefully lying down on his back, his belly rising up like a carnival balloon. The orderly pushes the trolley down the hall towards the surgery center. Midday has turned to 4 pm and the okay for the liver has finally come through. The light is golden, illuminating the particles in the air of each beam of light Jorge passes through. The clicking of the trolley wheels and soft steps of the orderly echo down the hall. Passing under a carved image of Christ suffering on the cross, they arrive at a thick metal door that swings open slowly, pushed outward by two nurses in blue scrubs, hairnets and masks covering their faces. Jorge is looking up at the ceiling, not making much eye contact with anyone. The doors close behind him.

An hour later, Jorge is anesthetized and only his distended belly can be seen jutting out from the blue surgical sheets over his lower body, and his chest and face. In the room next door, 2 doctors are preparing the healthy liver. Using thin metal tools they dissect and prepare it, as if they’re cutting fat from chicken. They identify the arteries and veins that will need to be sewn into the arteries and veins of Jorge’s body, and the portal veins through which a cooling solution is run to preserve the donated liver. They insert tubes and strings and hooks in the appropriate places. The liver is surprisingly large—it is the largest organ in the body and holds about 13 percent of one's blood at any given moment. This one, an example of a healthy liver, is wonderfully smooth, colored a red-grey like the wings of a sea ray.

It’s quiet in the room except for the buzzing of machinery and the chatting of the doctors, who look as if they’re two college students pouring over biology homework or young boys inspecting some curious creature found on the beach. It smells faintly, a light rubbery and chemical smell, not as pungent as you’d think the odor of a liver might be. One of the doctors loses grip of a long piece of fat. It springs away from the prong, making a slapping sound like a rubber band. He gets a hold of it again and both of them chuckle.

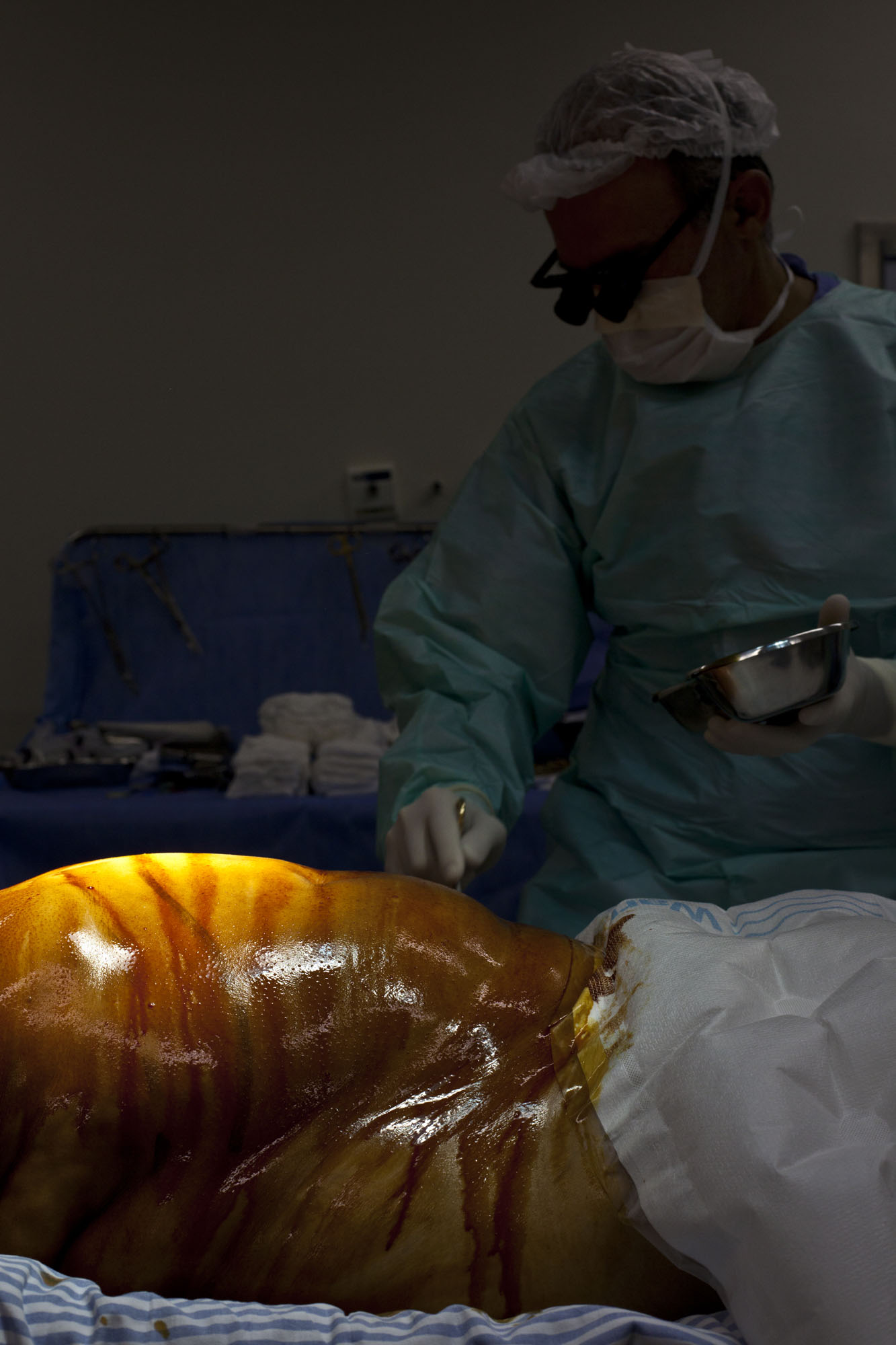

In the other room where Jorge lies asleep, the lead surgeon, Dr. Reinaldo Fernandes, has begun to burn through the skin of Jorge’s belly with a laser. The smell is like new plastic and formaldehyde. One surgeon separates the skin as Reinaldo works. There are a total of 7 professionals surrounding Jorge: 2 anesthesiologists, 3 surgeons and 2 nurses. They all chat amongst themselves, Reinaldo burning the layers of skin, a nurse passing tools to the surgeons, the anesthesiologists adjusting the levels of anesthesia and protein injected into Jorge’s body. To an observer, it is somehow difficult to keep in mind that this is a living breathing human body being burned and sliced literally to the core. However, this is a thought constant in the minds of the young and youngish men and women in the room, but it is not an overwhelming one. They never forget they are operating on a real person, and this is part of the excitement and meaningfulness of their job—not to mention a fact that never ceases to be “really cool,” as one anesthesiologist puts it.

Still, the lightness and chatter in the room seem at odds with the actual acts of this stage of the surgery. One of the surgeons sucks the belly fluid out through a tube. It’s a bit sickening: the burning and the sucking together. It’s horribly violent, how deep they are cutting into the body. But perhaps a little like soldiers who have experienced the gruesome scenes of war, humor has become a necessary distraction and a normalized response to such bloody sights—in fact it maintains their ability to keep calm and do their job to the best of their ability. A total of 11 liters of fluid is eventually sucked out of Jorge’s belly. The usual amount is 7.

They peel Jorge’s skin back, stretching it around metal prongs that will keep the belly flesh out of the way. All the layers of skin are visible now: the red and pink dermis and the yellow fat and connective tissue beneath that, thick and lumpy. The cavern that has opened up in Jorge’s body reveals his heart beating through the wall of his diaphragm, his spleen lifting up and down ever so slightly with his breathing. Reinaldo and the other surgeons do not turn away from their work. The hands of the nurse assisting them move quickly and constantly, putting each tool in their hands deftly, without them even having to turn a head. All three have become silent as they move deeper into the body, moving with the natural rhythms of Jorge’s breathing.

Dr. Renato, one of the anesthesiologists, says that Jorge has a higher risk of hemorrhage and reperfusion syndrome, two of the most common complications during a liver transplant, because of his history—Jorge’s disease left him with a MELD score of 16, a high score but also one that is low enough that he has a better chance of surviving the surgery and living long enough afterwards for the transplant to be worth it, though other patients may have even more acute cases of cirrhosis. Jorge is 51 years old and his donor was 40 at the time of his death—the only information the surgeons receive about the donor is his age, gender, and that he was declared brain dead the day before from a traumatic brain injury. They are not even told his name—there is no information to separate this man from any other donor, whose typical profile is something like this, death by traumatic brain injury or brain aneurism. All day and all night, all 7 days of the week, a team searches for livers via an online donor map and sometimes by going in person to various ICUs in search of patients who may soon become brain dead—it is a dark job. The surgeons, though, have no part in this search. Ethically, they are not allowed to. Their job is solely to deconstruct the body, insert the new liver, and put the body back together again.

* * *

After some time, Jorge’s liver is revealed. This organ looks particularly unhealthy: it is dark purple and lumpy, it looks sick and moldy. The cirrhosis has replaced the healthy liver tissue with scar tissue. The liver cells, blocked by the connective tissue created by the liver in its initial attempt at repairing itself (the first stage of scarring), can no longer do their job: carrying bile from the liver to the intestine where it is then disposed of. Though Jorge’s cirrhosis is caused by alcohol abuse, the damage to the liver caused by Hepatitis C is the same. The Hepatitis C virus invades the blood stream, slowly and quietly replacing the native hepatic cells until the liver becomes cirrhotic—scarred. This process can occur silently over a lifetime, which is why so many Hep C patients often don’t know they have the disease until they already have cirrhosis.

Like the damming of a river, the cirrhosis clogs the blood passages within the liver forcing the liver cells to find other clean channels by which they can return to the heart or jettison harmful substances out of the bloodstream. Over the passing of years, the cirrhotic liver gradually ceases to function completely, keeping it from performing such essential tasks as building and breaking down proteins, sugars, and fats that allow for proper immune system functioning, digestion of food, and elimination of waste products. Without a liver transplant, the dying liver will eventually cause the rest of the body to shut down, killing the person it was attempting to repair.

In the room next to the operating room, the new liver is now prepared. The doctors wrap it in a bag full of liquid and place it in a Tupperware container filled with ice. Pieces of fat are stretched across the metal top of the table. They lift the Tupperware container and place it into a big cooler also filled with ice, chatting with each other—their work is done for now. They wheel the cooler out of the room and the few yards down the hall to where Jorge’s diseased liver still remains in his body. They could just as easily be going to a picnic as delivering a liver to save, or rather extend, Jorge’s life.

A little after 7 pm, Dr. Lucio Pacheco comes into the operating room. He is o Chefe, chief liver transplant surgeon and head of a staff of 30 people (11 surgeons, 10 anesthesiologists, 8 hepatologists, and an infectologist) at Sao Francisco. “Boa noite, boa noite. Good evening, good evening,” he nods to everyone in the room, greeting them each by name. Three surgeons now surround Jorge, and they open a space for Dr. Lucio to sit and inspect the work done so far. He has arrived because it is almost time to make the swap—diseased liver for healthy.

* * *

When the time has finally come, a sour smell hangs in the air as the surgeons dig into the body with their hands, pulling back the liver as they carefully burn around it with a laser, which makes a white vapor rise up as they separate it from its surrounding organs and structures. The great veins and main arteries have been clamped to prevent blood from flowing to the diseased liver anymore. The smell gets stronger and stronger, like burning rubber and formaldehyde. Soon they pull the liver out in a swift movement and there is a sound like air escaping. They place the diseased liver into a metal pan. Jorge’s heart rate increases, and you can see it beating against his diaphragm even more clearly now that his liver is gone. At this moment, the anesthesiologists are essentially keeping Jorge alive, adjusting his levels, injecting him with more liquid protein. Dr. Renato checks or adjusts the monitors every few minutes, eyes interested and alert. He feels he is a pilot in a space ship, navigating the consciousness and bodily functions of Jorge’s body. An EKG displays the electrical activity of Jorge's heart. Beeping lines on a screen represent his pulmonary artery, central venous pressure, oximetry levels, capnography levels, and his level of consciousness—literally an adjustable number on a scale of 0-100, 100 being no electrical activity in the brain. The normal level of consciousness during surgery is between 42 and 60 and Jorge rests closer to 60. They monitor the percentage of oxygen saturation in his pulmonary arterial blood (SVO2), his cardiac output, blood coagulation—almost every single process necessary to the functioning of a human body. They have only a limited amount of time to complete the switch and connect the new liver to Jorge’s arteries and veins—a maximum of a few hours. Jorge’s heart is beating hard. The three surgeons place the healthy liver into the newly empty cavity together, their blood spattered gloved hands cradling it gently. “Beleza, beleza. Beautiful, beautiful.” murmurs Reinaldo.

* * *

The old liver sits in a pan in the other room. It used to be in Jorge’s body and now it sits in a pan. It is a dark and dead looking thing.

* * *

One of the surgeons steps outside for a break, rubbing his eyes. Now is time for the hardest part—to stitch the healthy liver in, artery to artery, vein to vein. By 11:00 pm the room has become almost silent. All that can be heard is the beeping of monitors and the steady beat of Jorge’s heart. Every once in a while Reinaldo lets out a big sigh and stretches. Then he returns to careful stitching. The new liver becomes redder as it gets stitched inside Jorge’s body, as Jorge’s blood begins to flow through it. His insides look brand new, beautiful and shiny.

Time passes. The work continues. The anesthesiologists peer over the tarp every once in a while to observe the progress. Periodically the nurses and anesthesiologists will drift in and out of the room, often high fiving each other when they return. Their backpacks are lined up against the wall. The anesthesiologists and a nurse check out a bike magazine excitedly and make jokes, chit chatting as they fill up a syringe.

After an hour and a half or so comes the easy part: stitching Jorge’s stomach back together. The surgeons’ hands move quickly, the nurse cuts the stitches in perfect timing with them. It is like knitting. The flaps of skin come together until they take the form of a stomach. The surgeons go back to chatting. The last stitch is put in at 12:45 in the morning. With the final stitch, Jorge’s anesthesia is just beginning to wear off. His changing consciousness level can literally be seen: his head moves back and forth at 40, his eyes flicker open and shut at 32. The anesthesiologists have taken the tarp from over his face and spread his arms wide—mirroring the Jesus’ on the Cross that hang throughout the hospital. Jorge opens his eyes and lets out a moan. The surgeons take the tubes from his mouth and he lets out a horrible wretch, opening and closing his left fist. His eyes open wide, he arches his back retching, saying over and over again “I want to die, let me die. I feel pain all over my body, let me die.” The surgeons just chat with each other—apparently this is a normal reaction for patients just waking from the fog of anesthesia after a major surgery. They are calm and gentle as they move Jorge from the operating table to a trolley. He continues to call out, “let me die, let me die,” head lolling back and forth, mouth opening wide as he arches his back, moaning hoarsely. His voice echoes softly down the hall as he is wheeled to the intensive care unit.

* * *

The post operation room is cool and quiet. All the patients are sleeping. It’s around 1:30 in the morning. A Sister, she calls herself Irma, paces the hallway, stopping in each patient’s room. She lives here in the hospital, passing her nights praying for the patients. By now, Jorge has calmed, and the orderlies move him from the trolley to the bed. At this moment Sister Irma crosses herself, whispering a prayer, while the orderly slowly closes the door behind him. Jorge will spend 5 days in the ICU, where he will take medicines to keep his body from rejecting his new liver, to keep the immune system calm after such an invasive surgery. Then he will remain in the hospital for up to a month so that the early parts of his recovery can be monitored closely by hospital staff. He will attend meetings for alcoholics and be set up for a recovery regimen upon his release. The doctors and nurses have done all they can, but in the end, disease, be it alcoholism or hepatitis C, will be the ultimate decider of whether or not this new liver will significantly improve or prolong the quality of the patient’s life.