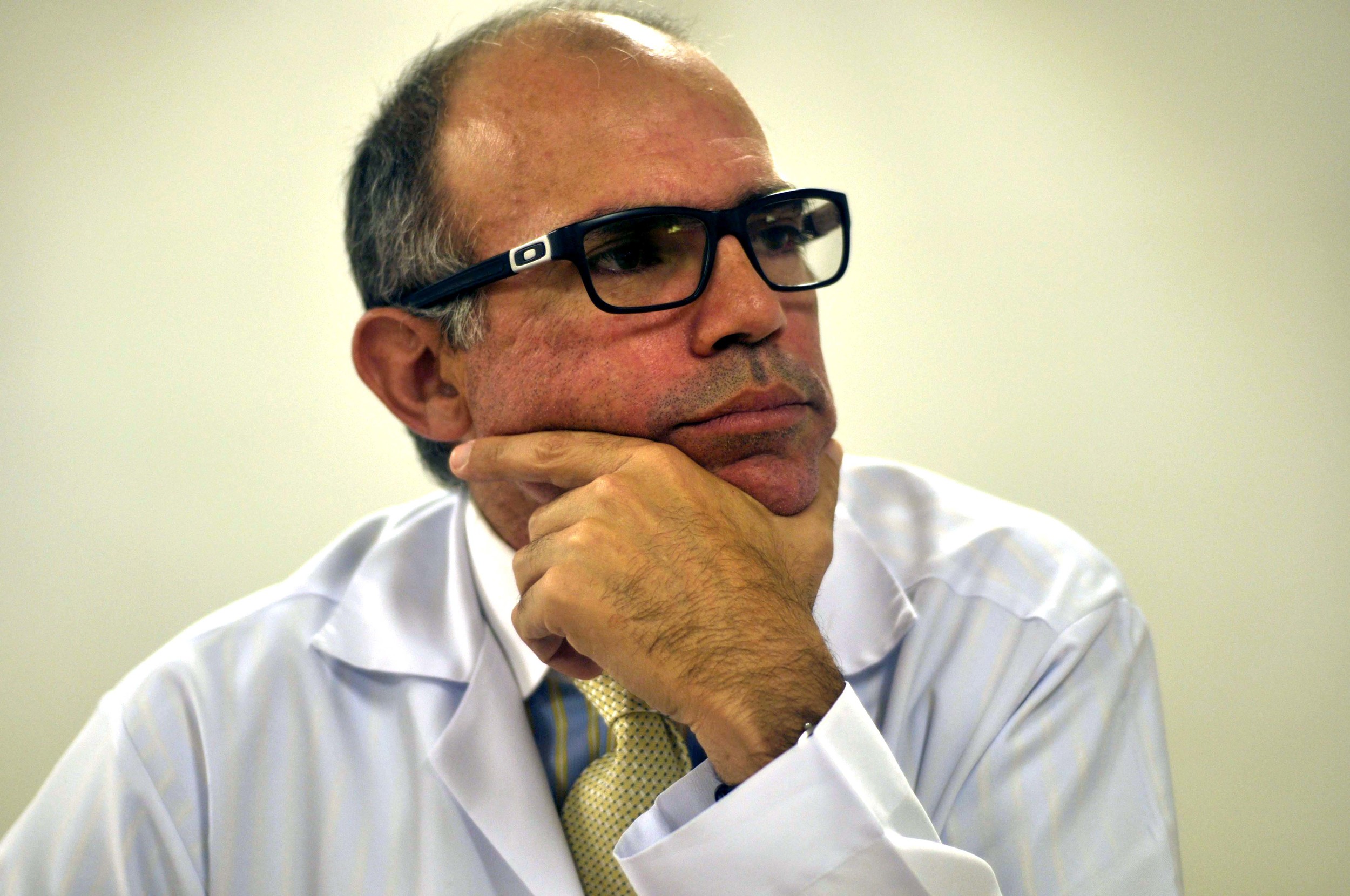

DR. LUCIO: THE SURGEON

Text and Audio by Erin Stone

Photograph by Lucas Andrade

Dr. Lucio Pacheco has a smaller frame than he appears to have in the pictures accompanying articles about his work or his curriculum vitae. His demeanor, however, makes him seem like a much larger man. He walks in long, measured steps and stands with a perfect posture: shoulders back, neck straight. He moves purposefully and composedly—at first glance it appears to be a leisurely, unhurried stroll but the quickness with which he reaches the other side of a room proves this is only a trick of the eye. His manner is calm; his eyes attentive. The combination of his warm smile and coolheaded air is both comforting and intimidating. You can imagine such a combination gives peace of mind to a patient: this man is a professional, but he is also a listener.

He is a liver surgeon—the chief liver surgeon, in fact, at Sao Francisco Hospital, the largest public hospital in Rio—which means that for his career he walks a thin line: one between survival and death. It is a line that can make it tempting to maintain a degree of separation between himself and his patients, but this temptation, Dr. Lucio knows, can create the gravest of dangers. Without a close relationship with his patient, a surgeon can easily make the wrong decision under pressure.

Livers can become available at any moment, and often they arrive with problems of their own: some livers may be in an earlier stage of hepatitis C than the patients whose bodies they are intended for. These livers are just healthy enough and may be the only ones that match the patient's genotype. Thus, Dr. Lucio must know his patients well. His patients must know all the risks of accepting a liver, in particular an imperfect one. And they both must be on the same page—that even if a liver becomes available after years of waiting and matches the patient’s genotype, if the patient’s MELD (Model for End-Stage Liver Disease) score has risen to a level that makes the surgery risk too great or the possibility of death shortly after too high, in the end it is Dr. Lucio who has the final say as to whether or not the liver will go to one patient or another.

After all, when it comes down to it, there are only two possible outcomes: to die or to get better for a little longer at least.

Dr. Lucio speaks levelly about this heavy responsibility he bears, and there is noticeable sadness in his tone. It is difficult to be the person who decides which of your patients does or does not receive a life-saving liver.

“The way you see life changes a lot knowing that you have a human life in your hands. When one of your patients dies it can be disastrous, and a lot of people will not understand it. When you’re always successful it is great, but when it comes to transplants, you won’t have success in many cases. You’ll have losses, and the transplant patient has a much closer relationship with the doctor than the regular ones that you talk one or two times a year. [Transplant surgeons] do the surgery and follow their patients’ lives. Sometimes you know the transplant patient more than one year before the surgery, and you’ll follow him for the next years, for his whole life. This explains why it is so hard to lose a patient during the transplant surgery. Even today I can’t handle this well. It’s a different way to do medicine. You have a very parallel life with your patients, and it makes you demand too much of yourself. A lot of doctors can’t live with this and they abandon this ‘transplant life.’ The ones who stay become different people. I have patients that knew my children when they were born and still I have contact with them now, twelve years after. All these years we keep in touch and take care. It’s different from any other medical speciality. There’s no way for you to be an arrogant surgeon, there’s no space for this kind of person. Maybe this is because of the big change [transplant surgeons must go through].”

Having done almost 1,000 liver transplants over the expanse of his career, Dr. Lucio says he could talk about moments that greatly impacted his life in probably half of them. His most dramatic experiences were related to patients with fulminant hepatatic failure, or acute liver failure, particularly children:

“My first baby transplant is now a teenager. She was a year and a half [when the surgery was done]. She had had no hope of getting to two years old. But now she is fourteen and a beautiful girl who can do everything in her life. This is one of the most memorable moments of my transplant life.”

He smiles, his happiness visible in the creases of his eyes. He talks of many of his patients—he remembers them all it seems. He tells of one woman, now 77 years old, who had her surgery when she was in her sixties and has been able to see the birth of her grandchildren because of her new liver. She got to help raise them, and she is still living well.

“So even though [being a liver transplant surgeon] is a hard profession, I can't think of myself doing anything else…It is different from any other medical specialty.”

Through all of this anguish and joy—throughout all of these lives—Dr. Lucio and other transplant surgeons like himself must also live with the fact that a liver transplant is not a cure. A liver transplant in a hepatitis C patient only guarantees an extended life, not an HCV free life. Even after the surgery, the virus remains in the blood so that almost all HCV-positive liver transplant patients, which accounts for most liver transplant patients, will be re-infected.

“So why do we do these transplants?” Dr. Lucio says with a shrug. “We do the transplant to treat the virus, to wait for a new kind of medicine. We can also try the conventional treatments [i.e. interferon], because there are patients that did not respond to the conventional treatment before the transplant and after the transplants they may be successfully treated. But in the last two international congresses about hep C and liver transplantation, much has been said about the great results of the new drugs for treating liver transplant patients with HCV. These drugs are pills, with much fewer side effects than the regular medicine. But there is a huge problem that makes them inaccessible—the price.”

Oral drugs like sofosbuvir (brand name Sovaldi) are the best chance for late-stage hepatitis C patients who have already gone through a liver transplant and suffered the side effects of interferon treatment with unsuccessful results. Sofosbuvir costs about $84,000 in the United States for its 12-week treatment, putting the drug at $1,000 a pill. Though Gilead Sciences, the pharmaceutical company that created sofosbuvir, recently announced that it would issue licenses to sell cheaper versions of sofosbuvir in 91 countries, this positive step towards accessibility has a hidden negative. The designated countries exclude some of the countries with the greatest majorities of people living with hepatitis C—like Brazil, which is a middle income country with one of the highest rates of HCV in the world. Thus, it could take decades before sofosbuvir enters the market as an affordable generic.

Though Dr. Lucio is hopeful for oral drugs like sofosbuvir to become more accessible to his patients soon, he knows that it may be while. He is accustomed to these ups and downs by now, but this does not get in the way of his work, though there were more than a few times in his almost 20 years of being a liver transplant surgeon that Dr. Lucio felt the pressures and rollercoaster ride of “transplant life” overwhelm him.

“I thought about giving up not one or two times, but several times. Now I occupy a delicate position. I need to keep the younger doctors from giving up, and this does not mean I'm not affected by the losses. I think I will never be able to handle the losses. Now I suffer in a more internal way because I need to support the younger doctors. I need to keep the team going so that we can attend to the other patients that need us.”